#nonukes

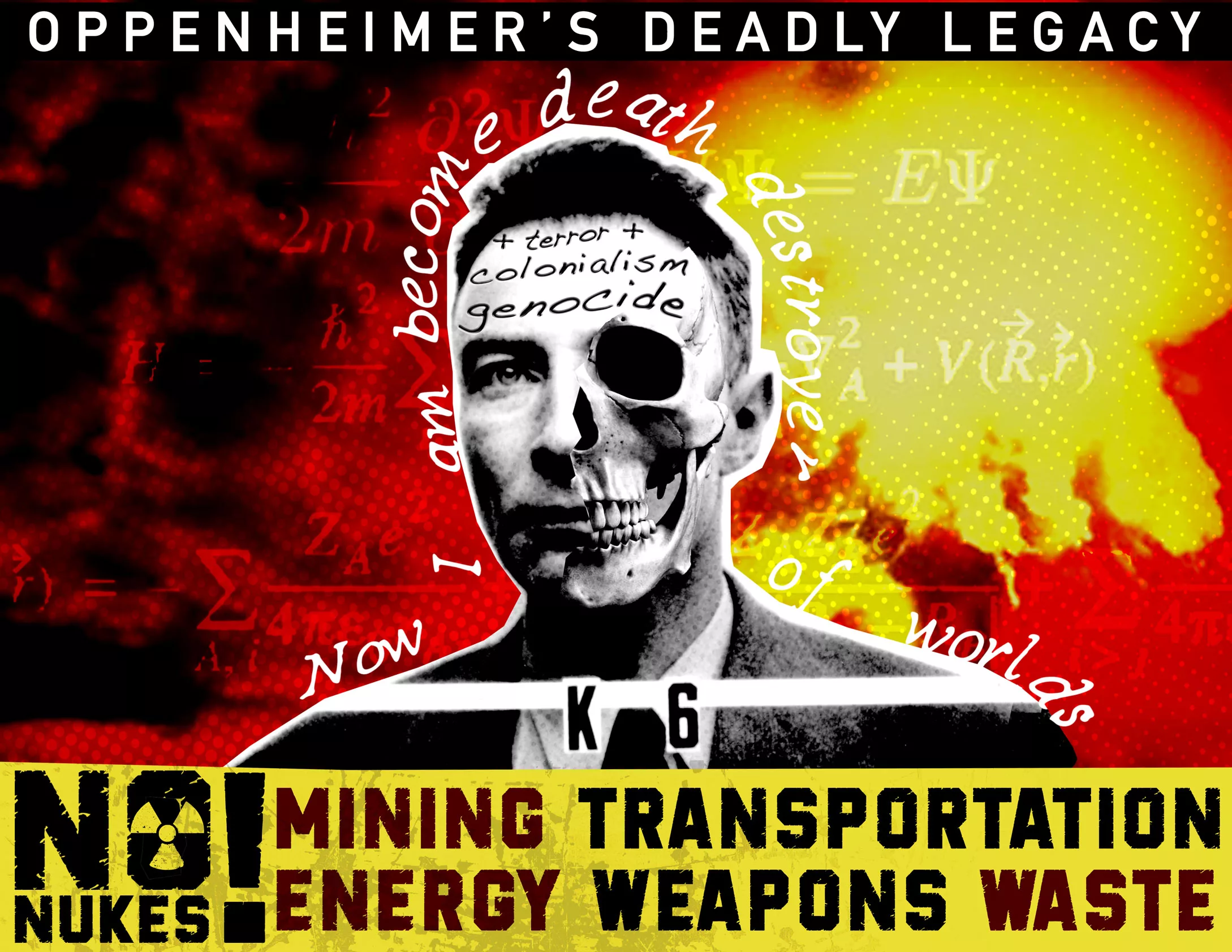

Architect of Annihilation: Oppenheimer’s Deadly Legacy of Nuclear Terror

Published

2 years agoon

By

Rudy

Read our quick and dirty review of the movie here.

Klee Benally, Indigenous Action/Haul No!

Contributions by Leona Morgan, Diné No Nukes/Haul No!

Printable posters (PDFs): 11″x17″ color, 11″x17″ black & white

The genocidal colonial terror of nuclear energy and weapons is not entertainment.

To glorify such deadly science and technology as a dramatic character study, is to spit in the face of hundreds of thousands of corpses and survivors scattered throughout the history of the so-called Atomic age.

Think of it this way, for every minute that passes during the film’s 3-hour run time, more than 1,100 citizens in the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki died due to Oppenheimer’s weapon of mass destruction. This doesn’t account for those downwind of nuclear tests who were exposed to radioactive fallout (some are protesting screenings), it doesn’t account for those poisoned by uranium mines, it doesn’t account for those killed during nuclear power plant melt-downs, it doesn’t account for those in the Marshall Islands who are forever poisoned.

For every second you sit in the air conditioned theater with a warm buttery popcorn bucket in your lap, 18 people dead in the blink of an eye. Thanks to Oppenheimer.

Though you’ll certainly learn enough about J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” thanks to director Christopher Nolan’s 70mm IMAX odyssey, let’s be clear about his deadly legacy and the overall military and scientific industrial complex behind it.

After the successful detonation of the very first atomic bomb, Oppenheimer infamously quoted the Hindu scripture Bhagavad-Gita, “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.” Barely a month later, the “U.S” dropped two atomic bombs devastating the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and more than 200,000 people were killed. Some of the shadows of those perished were burned into the streets. One survivor, Sachiko Matsuo, relayed their thoughts as they tried to make sense of what was happening when Nagasaki was struck, “I could see nothing below. My grandmother started to cry, ‘Everybody is dead. This is the end of the world.” A devastation that Nolan intentionally leaves out because, according to the director, the film is not told from the perspectives of those who were bombed, but by those who were responsible for it. Nolan casually explains, “[Oppenheimer] learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on the radio, the same as the rest of the world.”

Months after the atomic detonation at the “Trinity” site in occupied Tewa lands of New Mexico, Oppenheimer resigned. He walked away expressing the conflict of having, “blood on his hands,” (though reportedly he later said the bombings were not “on his conscience”) while leaving a legacy of nuclear devastation and radioactive pollution permanently poisoning lands, waters, and bodies to this day.

U.S. military and political machinery cannibalized the scientist and turned him into a villain of their imperialist cold-war anxiety. They reminded him and the other scientists behind the Manhattan Project, that they and their interests were always in control.

Oppenheimer never was a hero, he was an architect of annihilation.

The race to develop the first atomic bomb (after Nazis had split the atom) never could be a strategy of peaceful deterrence, it was a strategy of domination and annihilation.

Nazi Germany was committing genocide against Jewish people while the U.S. sat on the political sidelines. It wasn’t until they were directly threatened that the U.S. intervened. Though Nazi Germany was defeated on May 8th, 1945, the U.S. dropped two separate atomic bombs on the non-military targets of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6th and 9th, 1945.

To underscore Oppenheimer’s complicity, he suppressed a petition by 70 Manhattan Project scientists urging President Truman not to drop the bombs on moral grounds. The scientists also argued that since the war was nearing its end, Japan should be given the opportunity to surrender.

Today there are approximately 12,500 nuclear warheads in nine countries with almost 90 percent of them held by the U.S. and Russia. It is estimated that 100 nuclear weapons is an “adequate… deterrence” threshold for the “mutually assured destruction” of the world.

Oppenheimer built the gun that is still held to the head of everyone who lives on this Earth today. Throughout the decades after the development of “The Bomb,” millions throughout the world have rallied for nuclear disarmament, yet politicians have never taken their fingers off the trigger.

The Deadly Legacy of Nuclear Colonialism

Nuclear weapons production and energy would not be possible without uranium.

Global uranium mining boomed during and after World War II and continues to threaten communities throughout the world.

Today, more than 15,000 abandoned uranium mines are located within the so-called U.S., mostly in and around Indigenous communities, permanently poisoning sacred lands and waters with little to no political action being taken to clean up their deadly toxic legacy.

Indigenous communities have long been at the front lines of the struggle to stop the deadly legacy of the nuclear industry. Nuclear colonialism has resulted in radioactive pollution that has poisoned drinking water systems of entire communities like Red Shirt Village in South Dakota and Sanders in Arizona. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has closed more than 22 wells on the Navajo Nation where there are more than 523 abandoned uranium mines. In Ludlow, South Dakota an abandoned uranium mine sits within feet of an elementary school, poisoning the ground where children continue to play to this day.

Nuclear colonialism has ravaged our communities and left a deadly legacy of cancers, birth defects, and other serious health consequences, it is the slow genocide of Indigenous Peoples.

From 1944 to 1986 some 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from mines on Diné lands. Diné workers were told little of the potential health risks with many not given any protective gear. As demand for uranium decreased the mines closed, leaving over a thousand contaminated sites. To this day none have been completely cleaned up.

On July 16, 1979, just 34 years after Oppenheimer oversaw the July 16, 1945 Trinity test, the single largest accidental release of radioactivity occurred on Diné Bikéyah (The Navajo Nation) at the Church Rock uranium mill. More than 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive tailings poured into the Puerco River when an earthen dam broke. Today, water in the downstream community of Sanders, Arizona is poisoned with radioactive contamination from the spill.

Although uranium mining is now banned on the reservation due to advocacy from Diné anti-nuclear organizers, Navajo politicians have sought to allow new mining in areas already contaminated by the industry’s toxic legacy. It is estimated that 25% of all the recoverable uranium remaining in the country is located on Diné Bikéyah.

Though there has never been a comprehensive human health study on the impacts of uranium mining in the area, a focused study has detected uranium in the urine of babies born to Diné women exposed to uranium.

Western Shoshone lands in so-called Nevada, which have never been ceded to the “U.S.” government, have long been under attack by the military and nuclear industries.

Between 1951 and 1992 more than 1,000 nuclear bombs have been detonated above and below the surface at an area called the Nevada Test Site on Western Shoshone lands which make it one of the most bombed nations on earth. Communities in areas around the test site faced severe exposure to radioactive fallout, which caused cancers, leukemia & other illnesses. Those who have suffered this radioactive pollution are collectively known as “Downwinders.”

Western Shoshone spiritual practitioner Corbin Harney, who passed on in 2007, helped initiate a grassroots effort to shutdown the test site and abolish nuclear weapons. He once said, “We’re not helping Mother Earth at all. The roots, the berries, the animals, are not here anymore, nothing’s here. It’s sad. We’re selling the air, the water, we’re already selling each other. Somewhere it’s going to come to an end.”

Between 1945 and 1958, sixty-seven atomic bombs were detonated in tests conducted in Ṃajeḷ (the Marshall Islands). Some Indigenous people of the islands have all together stopped reproducing due to the severity of cancer and birth defects they have faced due to radioactive pollution.

In 1987 the “U.S.” congress initiated a controversial project to transport and store almost all of the U.S.’s toxic waste at Yucca Mountain located about 100 miles northwest of so-called Las Vegas, Nevada. Yucca Mountain has been held holy to the Paiute and Western Shoshone Nations since time immemorial. In January 2010 the Obama administration approved a $54 billion dollar taxpayer loan in a guarantee program for new nuclear reactor construction, three times what Bush previously promised in 2005.

There are currently 93 operating nuclear reactors in the so-called U.S. that supply 20% of the country’s electricity. There are nearly 90,000 tons of highly radioactive spent nuclear waste stored in concrete dams at nuclear power plants throughout the country with the waste increasing at a rate of 2,000 tons per year.

From the 1979 disasters of Three Mile Island and Churchrock to the 1986 Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant melted down, the nuclear industry has been wrought with mass catastrophes with permanent global consequences.

In 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant catastrophically failed and began melting down after it was hit by an earthquake and tsunami. It’s been reported that the Fukushima plant has been leaking approximately 300 tons of radioactive water into the ocean every day. Today, the Japanese government is open about its plans to release remaining radioactive waters into the Pacific.

“Depleted Uranium” weapons deployed by the U.S. in imperialist wars (particularly Iraq and Afghanistan) have also poisoned eco-systems, including at proving grounds and firing ranges in Arizona, Maryland, Indiana and Vieques, Puerto Rico. Depleted uranium is a by-product of uranium enrichment process when it’s used for nuclear reactor fuel and in the making of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear energy production is now claimed as a “green solution” to the climate crisis, but nothing could be further from the truth of this deadly lie.

In April 2022, the Biden administration announced a $6 billion government bailout to “rescue” nuclear power plants at risk of closing. A colonial government representative stated, “U.S. nuclear power plants contribute more than half of our carbon-free electricity, and President Biden is committed to keeping these plants active to reach our clean energy goals.” They, along with Climate Justice activists cite nuclear energy as necessary to combat global warming, all while ignoring the devastating permanent impacts Indigenous Peoples have faced.

Due to this “greenwashing” of nuclear energy, we face a push for nuclear hydrogen, small modular nuclear reactors, and High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium (HALEU) driving a renewed threat of new uranium mining, transportation, & processing.

Though the Obama administration placed a moratorium on thousands of uranium mine leases around the Grand Canyon in 2012, pre-existing uranium claims were allowed. Environmental groups and Indigenous Nations are currently attempting to make the moratorium permanent and push for a new national monument, yet these will do little to nothing for the handful of pre-existing uranium mines that have been allowed to move forward.

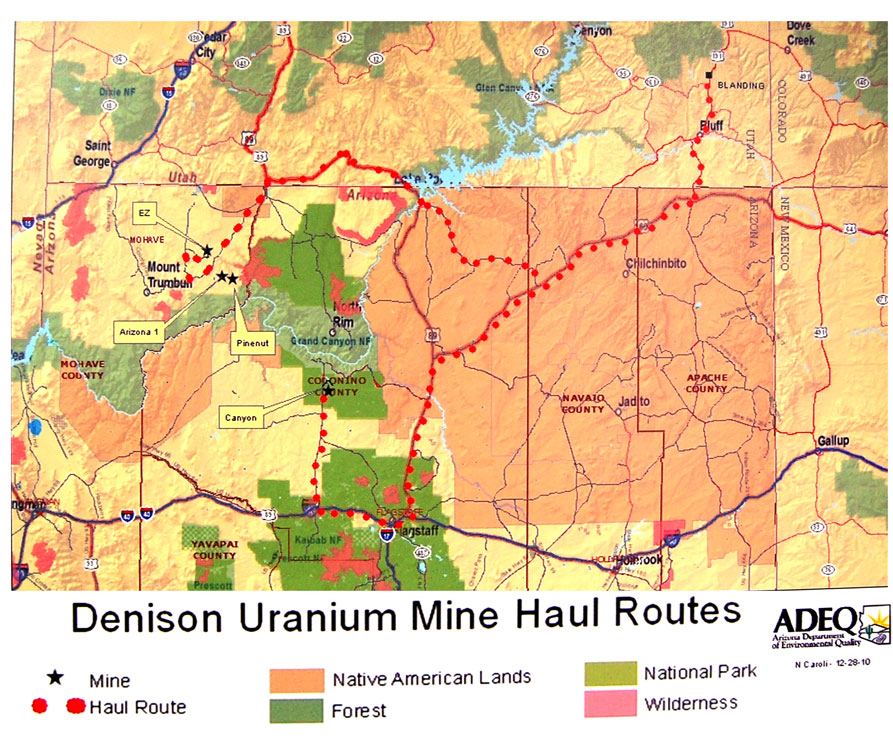

Despite these actions, underground blasting & above ground work has begun at Pinyon Plain/Canyon Mine, just miles from the Grand Canyon. Once Energy Fuels, the company operating the mine, starts hauling out radioactive ore, they plan to transport 30 tons per day through Northern Arizona to the company’s processing mill in White Mesa, 300 miles away.

The White Mesa Mill is the only conventional uranium mill licensed to operate in the U.S. The mill was built on sacred ancestral lands of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe near Blanding, Utah. Energy Fuels disposes radioactive and toxic waste tailings in “impoundments” that take up about 275 acres next to the mill. Since there are limited radioactive waste facilities, White Mesa Mill has become an ad hoc dump for the world’s nuclear wastes that have no final repository.

In so-called New Mexico, a state addicted to nuclear monies for both nuclear weapons and energy facilities, there are two national nuclear labs and two national waste facilities. Along with legacy uranium mines and mills, there was Project Gasbuggy (an underground detonation), a “Broken Arrow” accident near Albuquerque, and countless tons of radioactive waste buried in unlined pits, Pueblo kivas, and watersheds. Currently, there are planned expansions and modifications at Los Alamos National Labs, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, and Urenco uranium enrichment facility. Most recently, the state has been threatened by two newly licensed consolidated interim storage facilities for “spent fuel” from nuclear power plants in New Mexico and Texas. The federal government continues to push nuclear projects with financial incentives.

Nuclear proliferation continues as the U.S. allows uranium miners and others who are eligible for the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to die. Many continue to suffer and wait for compensation funds to be allocated or are not eligible due to the limitations of the act.

The devastation of nuclear colonialism, which permanently destroys Indigenous communities throughout the world, is not entertainment. This is the terrifying legacy of nuclear energy and weapons that movies like Oppenheimer and duplicitous climate justice activists advocate.

Indigenous Peoples live, suffer, and continue to resist its consequences every day.

END NUCLEAR COLONIALISM!

###

Recommended links:

https://haulno.com

http://www.dinenonukes.org

https://tewawomenunited.org/programs/environmental-health-and-justice-program

https://stopforeverwipp.org/home

https://www.trinitydownwinders.com/

http://www.cleanupthemines.org

https://www.nirs.org/

https://www.radioactivewastecoalition.org

https://www.dont-nuke-the-climate.org/

https://www.nuclear-heritage.net/index.php?title=Nuclear_Heritage_Network

https://yukiyokawano.com

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vBO_C6GkIpM&t=10s

https://apjjf.org/2022/1/Schattschneider-Auslander.html

Articles:

Red Water Pond Road

https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/a-radioactive-legacy-haunts-this-navajo-village-which-fears-a-fractured-future/2020/01/18/84c6066e-37e0-11ea-9541-9107303481a4_story.html

ABQ Museum

https://www.abqjournal.com/lifestyle/arts/albuquerque-museums-online-exhibit-trinity-takes-a-look-at-the-aftermath-of-the-atomic-bomb/article_33d17c15-61c8-5e1f-b32c-99f4ebee5db4.html

You may like

-

The family of Klee Benally thanks you for the donations!

-

No Thanks, No Giving! Indigenous Action Yearly Fundraiser (online)

-

16th Annual No Thanks, No Giving!

-

New Book: No Spiritual Surrender, Klee Benally

-

Indigenous Action Podcast Episode 17: Decolonization isn’t a Holiday

-

Do “We keep us safe”? Notes on Action Security & Some Resources

#nonukes

A quick & dirty review of the movie Oppenheimer

Published

2 years agoon

July 20, 2023By

Rudy

We watched this movie after arguing with social media pro-nuke apologists who accused us of being ill-informed as not having viewed Christopher Nolan’s biopic, so excuse the mess… (and if you haven’t already, read our initial post here for the context).

Oppenheimer is a glorification of the “complicated genius” and ambitions of white men making terrible decisions that imperil the world.

Many have remarked that the film is not a glorification, yet Christopher Nolan himself says, “Like it or not, J Robert Oppenheimer is the most important person who ever lived.”

Some of you may have even had a burst of laughter during the scene where Truman asked Oppenheimer what he thought the fate of Los Alamos should be and “Oppie” retorted, “Give the land back to the Indians.” But alas, the poisoned scarred landscape today is host to a 10-day “Oppenheimer Festival.” To underscore the disconnect of legacies, a small commemoration near the Churchrock spill site was also held on the anniversary of the Trinity detonation, a few hundred miles away. Yes, what glorification?

The movie is basically a Western à la John Wayne. It very well could have been called, “The Trial of the Sheriff of Los Alamos.”

Oppenheimer rides his horse with a black hat on and pulls a poster down from a fence post. He then strides into a debate on the “Impact of the gadget on civilization.” To respond to the question of how scientists can justify using the Atom Bomb on human beings, Oppenheimer speaks, “We’re theorists yes, we imagine a future and our imaginings horrify us. They won’t fear it until they understand it and they won’t understand it until they’ve used it. When the world learns the terrible secret of Los Alamos our work here will ensure a peace mankind has never seen. A peace based on international cooperation.”

Nolan establishes the only narrative that matters is his attempt at historical redemption, he paints Oppenheimer as a victim. While perhaps not as depoliticized as Nolan alluded to in interviews (as the politics of American loyalty and the Red Scare drive the drama), the consequences of nuclear weapons and energy is barely considered (arguably barely at all considering the issue). This is a political omission of the most insidious sort and the film is even worse for it.

The movie cares more about constructing and clearing Oppenheimer as a victim of McCarthyism than the impacts of the atomic bomb and its deadly legacy of nuclear colonialism. As it’s stated, there’s a “Price to be paid for genius.” Everything else is dramatic notation. Nolan gives Oppenheimer the public hearing he feels like he was denied to ultimately prove he was an American patriot. In the end, the question “Would the world forgive you if you let them crucify you?” matters above all other concerns. The movie poses the argument as “science versus militarism” while the world and Indigenous Peoples continue to suffer the permanent consequences of nuclear weapons and energy in silence. A deadly silence more deafening than Nolan’s cinematic portrayal of the Trinity test. But hey, there’s even a minute of cheering after the test.

Nolan has us listening to the radio while two cities are destroyed and hundreds of thousands of lives are taken. Nolan keeps the camera on his lead actor’s face while the horrors of his bomb are shown on slides. Oppenheimer simply looks away. What more about this film do we need to know?

15,000 abandoned uranium mines poisoning our bodies, lands, and water. 1,000 bombs detonated on Western Shoshone lands… the list goes on (we only stop here because we’ve stated much more in our original post). All omitted and sentenced to suffer in catastrophic silence. Films like Oppenheimer are only possible because people keep looking away from the deadly reality of nuclear weapons and energy.

#mmiwgt2s

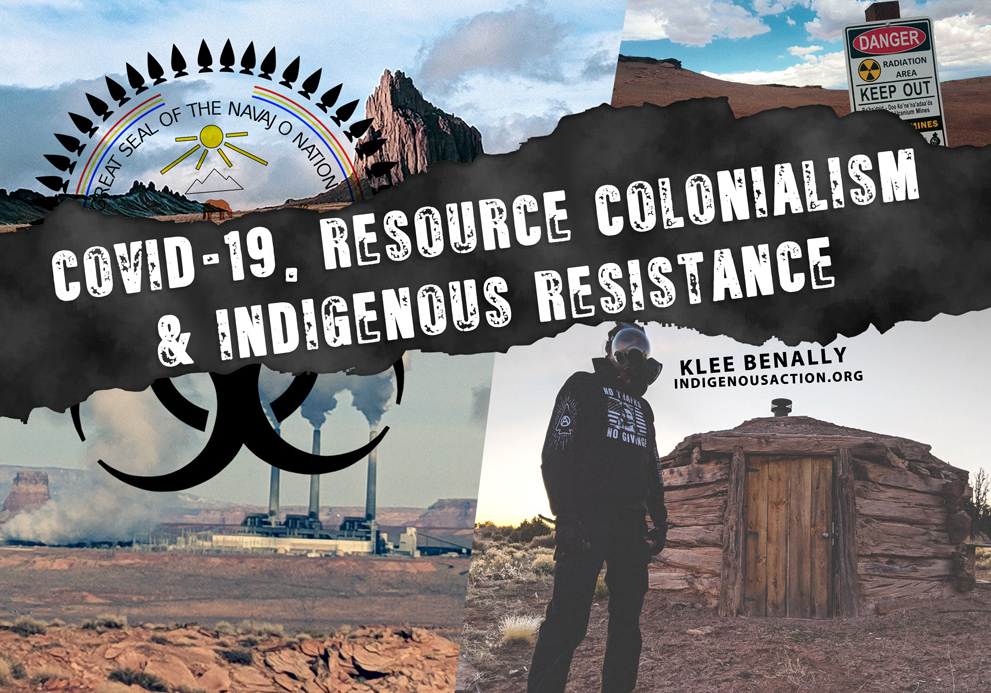

COVID-19, Resource Colonialism & Indigenous Resistance

Published

4 years agoon

April 22, 2021By

Rudy

Note: This was originally written May 2020 & published in part in Black Seed #8.

This version has been slightly revised & updated.

Klee Benally, IndigenousAction.org

www.patreon.com/kleebenally

Diné Bikéyah (The Navajo Nation) has faced and endured the highest rate per-capita of COVID-19 cases than any settler colonial U.S. state.

As this respiratory virus wreaks havoc through these lands, mainstream media has again anointed our people as the mascots of poverty and victimization. The statistics are pounded loudly to evoke settler pity: Approximately 33% of our people have no running water or electricity. We live in a “food desert” with 13 grocery stores serving nearly 200,000 residents. Diné Bikéyah has approximately 50% unemployment. While these facts are not wrong, the solution is not more fundraisers for the “poor Indians.”

As this respiratory virus wreaks havoc through these lands, mainstream media has again anointed our people as the mascots of poverty and victimization. The statistics are pounded loudly to evoke settler pity: Approximately 33% of our people have no running water or electricity. We live in a “food desert” with 13 grocery stores serving nearly 200,000 residents. Diné Bikéyah has approximately 50% unemployment. While these facts are not wrong, the solution is not more fundraisers for the “poor Indians.”

Has this pandemic impacted our people so disproportionately simply because we merely lack power lines and plumbing? Is it just because there aren’t massive corporate stores on every corner of our reservation? Would we really be that much more immune from this disease if every member of our tribe just had a job?

Dehumanizing narratives have always been part of the scenery here in the arid Southwest. If you blink on your way to the Grand Canyon, it’s easy to miss the ongoing brutal context of colonization and the expansion of capitalism. We live here and we even don’t see it ourselves. We’re too busy putting up that “Nice Indians Behind You” sign.

As Navajo Nation politicians impose strict weekend curfews, prohibit ceremonial gatherings, and restrict independent mutual aid relief efforts. As notoriously racist so-called reservation “border towns” like “Gallup, New Mexico” dispose of infected unsheltered relatives and initiate “Riot Act Orders” to restrict the influx of Diné who rely on supplies held in their corporate stores, the specter of the reservation system’s historical purpose haunts like a neglected ghost, pulling at our every breath, clinging to our bones.

What is omitted from the fever-pitched spectacle of COVID-19 disaster tourism, is that these statistics are due to ongoing attacks on our cultural ways of life, autonomy, and by extension our self and collective sufficiency.

While economic deprivation and resource scarcity are realities we face, our story is much more complex and more powerful than that, it’s a story of the space between harmony and devastation. It’s the story of our ancestors and of coming generations. It’s a story of this moment of Indigenous mutuality and resistance.

The Navajo Resource Colony & COVID-19

Colonial violence and violence against the earth has made our people more susceptible to viruses such as COVID-19.

While the COVID-19 virus spreads unseen throughout our region, a 2,500-square-mile cloud of methane is also concealed, hovering over Diné lands here in the “Four Corners” area. NASA researchers have stated, “the source is likely from established gas, coal, and coalbed methane mining and processing.” Methane is the second most prevalent greenhouse gas emitted in the so-called “United States” and can be up to 84 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Two massive coal fired power plants, the San Juan Generating Station and the Four Corners Power Plant operate in the area. If regarded as a single entity, the two plants are the second largest consumer of coal in the “U.S.” Most of the generated power is transmitted right over and passed reservation homes to power settler colonies in “Arizona, Nevada and California.”

It’s not news that over time, breathing pollution from sources such as coal fired power plants damages the lungs and weakens the body’s ability to fight respiratory infections. U.S. settler universities and news outlets have acknowledged that exposure to air pollution is correlated with increased death rates from COVID-19. At the same time, the EPA has relaxed environmental regulations on air polluters in response to the pandemic, opening the door for colonial imposed resource extraction projects on Diné lands to intensify their efforts.

According to a recent report titled, “Exposure to air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States,” COVID-19 patients in areas impacted by high levels of air pollution before the pandemic are more likely to die from the virus than patients in other parts of the “U.S.”

The New York Times published an article on the report stating that, “A person exposed to high levels of fine particulate matter is 15 percent more likely to die from the coronavirus than someone in a region with just one unit less of the fine particulate pollution.”

The report further states that, “Although the epidemiology of COVID-19 is evolving, we have determined that there is a large overlap between causes of deaths of COVID-19 patients and the diseases that are affected by long-term exposure to fine particulate matter.” The report also noted that, “On March 26, 2020 the US [Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)] announced a sweeping relaxation of environmental rules in response to the coronavirus pandemic, allowing power plants, factories and other facilities to determine for themselves if they are able to meet legal requirements on reporting air and water pollution.”

According to Navajo Nation Oil and Gas Company’s (NNOGC) website, “In 1923, a Navajo tribal government was established primarily for the Bureau of Indian Affairs to approve lease agreements with American oil companies, who [sic] were eager to begin oil operations on Navajo lands.”

Arguably, nearly every economic decision that the tribal government has made since then (with few exceptions) has facilitated further exploitation of Mother Earth for profit.

For every attack on Mother Earth waged by colonial entities, Diné have organized fiercely to protect Nahasdzáán dóó Yádilhil Bits’áádéé Bee Nahaz’áanii or the Diné Natural Law.

Groups like Diné CARE have been mobilizing since the late 1980s to confront ecological and cultural devastation. Adella Begaye and her husband Leroy Jackson organized to protect the Chuska Mountains from logging by the Navajo Tribal government. They formed Diné CARE and challenged the operations. Jackson had reportedly obtained documents that showed Bureau of Indian Affairs officials were underhandedly working to get the tribe exempt from logging restrictions designed to protect endangered species in the area. He was found murdered shortly after.

In defiance of efforts by Diné environmental groups such as Diné CARE to stop coal mining and power plants in the face of global warming, former Navajo Nation Council Speaker Lorenzo Bates declared, “war on coal is a war on the Navajo economy and our ability to act as a sovereign Nation.” At the time, the coal industry was responsible for 60% of the Navajo Nation’s general revenues. Bates stated that “These revenues represent our ability to act as a sovereign nation and meet our own needs.”

At the cost of our health and destruction of Mother Earth, politicians on the Navajo Nation have perpetuated and profited from coal-fired power plants and strip mines that have caused forced relocation of more than 20,000 Diné from Black Mesa and severe environmental degradation.

For forty-one years Peabody coal, which operated two massive strip mines on Black Mesa, consumed 1.2 billion gallons a year of water from the Navajo aquifer beneath the area. Although the mines are now closed and the Navajo Generating Station (NGS) coal-fired power plant they fed is also shuttered, the impacts to health, the environment, and vital water sources in the area have been severe. The NGS project was initially established with the purpose of providing power to pump water to the massive metropolitan areas of Phoenix and Tucson. For decades, while powerlines criss-crossed over Diné family’s homes and water was pumped hundreds of miles away for swimming pools and golf courses, thousands of Diné went without running water and electricity.

Diné environmental groups such as Black Mesa Water Coalition and Tó Nizhóní Ání’, who have long resisted resource colonialism on Dził Yijiin (Black Mesa), recently celebrated the shutdown of NGS while the Navajo Nation scrambled to keep the outdated power plant operating arguing that it was vital to the Navajo economy. What was ignored in the melee was that the owners and operators of the coal fired power plant were motivated to shift towards natural gas that has become cheaper due to fracking.

In 2019 the Navajo Nation further doubled down on coal by purchasing three coal mines in the Powder River Basin area located in so-called Wyoming and Montana. Approximately 40 percent of the so-called U.S.’s coal comes from the area, contributing to more than 14 percent of the total carbon pollution in the “U.S.” The deal also forced the Navajo Transitional Energy Company (NTEC) to waive its sovereign immunity as a condition to buy the mines from a company that had just declared bankruptcy.

Today there are currently more than 20,000 natural gas wells and thousands more proposed in and near the Navajo Nation in the San Juan Basin, a geological structure spanning approximately 7,500 square miles in the Four Corners. The US EPA identifies the San Juan Basin as “the most productive coalbed methane basin in North America.” In 2007 alone, corporations extracted 1.32 trillion cubic feet of natural gas from the area, making it the largest source in the United States. Halliburton, who “pioneered” hydraulic fracturing in 1947, has initiated “refracturing” of wells in the area. Fracking also wastes and pollutes an extreme amount of water. A single coalbed methane well can use up to 350,000 gallons, while a single horizontal shale well can use up to 10 million gallons of water. As I’ve mentioned previously, this is a region with approximately 30 percent of households without access to running water.

The San Juan Basin is also viewed as “the most prolific producer of uranium in the United States.” Uranium is a radioactive heavy metal used as fuel in nuclear reactors and weapons production. It is estimated that 25% of all the recoverable uranium remaining in the country is on Diné Bikéyah.

During the so-called “Cold War,” Diné lands were heavily exploited by the nuclear industry. From 1944 to 1986 some 30 million tons of uranium ore were extracted from mines. Diné workers were told little of the potential health risks with many not given any protective gear. As demand for uranium decreased the mines closed, leaving over a thousand contaminated sites. To this day none have been completely cleaned up.

In 1979 the single largest accidental release of radioactivity occurred on Diné Bikéyah at the Church Rock uranium mill. More than more than 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive tailings poured into the Puerco River when an earthen dam broke. Today, water in the downstream community of “Sanders, Arizona” is poisoned with radioactive contamination from the spill.

In 1979 the single largest accidental release of radioactivity occurred on Diné Bikéyah at the Church Rock uranium mill. More than more than 1,100 tons of solid radioactive mill waste and 94 million gallons of radioactive tailings poured into the Puerco River when an earthen dam broke. Today, water in the downstream community of “Sanders, Arizona” is poisoned with radioactive contamination from the spill.

Although uranium mining is now banned on the reservation due to advocacy from Diné anti-nuclear organizers, Navajo politicians recently sought to allow new mining in areas already contaminated by the industry’s toxic legacy.

In 2013 Navajo Nation Council Delegate Leonard Tsosie proposed a resolution to undermine the ban, his efforts were shut down by Diné No Nukes, a grassroots organization “dedicated to create a Navajo Nation that is free from the dangers of radioactive contamination and nuclear proliferation.” There are more than 2,000 estimated toxic abandoned uranium mines on and around the Navajo Nation. Twenty-two wells that provide water for more than 50,000 Diné have been closed by the EPA due to high levels of radioactive contamination. The recent push for nuclear power as “clean energy” has made the region more vulnerable to new uranium mining, including an in situ leach mine (which uses a process similar to fracking) right next to Mt. Taylor, one of the six Diné holy mountains.

Exposure to uranium can occur through the air, water, plants and animals and can be ingested, breathed in or absorbed through the skin. Although there has never been a comprehensive human health study on the impacts of uranium mining in the area, the EPA states that exposure to uranium can impair the immune system, cause high blood pressure, kidney disease, lung and bone cancer, and more. An ongoing effort called the Navajo Birth Cohort Study has also detected uranium in the urine of babies born to Diné women exposed to uranium.

In the book Bitter Water: Diné Oral Histories of the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute, Roberta Blackgoat, my grandmother and a matriarch of Diné resistance to forced relocation on Black Mesa, stated, “The Coal they strip mine is the earth’s liver. The earth’s internal organs are dug up. Mother Earth must sit down. The uranium they dug up for energy was her lungs. Her heart and her organs are dug up because of greed. It is smog on the horizons. Her breath, her warmth, is polluted now and she is angry when Navajos talk of their sickness. The coal dust in winter blows in to blanket the land like a god down the canyons. It is very painful to the lungs when you catch a cold. The symptoms go away slowly when dry coal dust blows in from strip mining. The people say the uranium can dry up your heart. No compassion is left for the motherland. We’ve become her enemy.”

Diné elders who have resisted forced relocation on Black Mesa have faced constant attacks on their ways of life, particularly through confiscation of livestock. The systematic destruction of Indigenous subsistence lifeways throughout Diné Bikéyah has been a strategy waged since the beginning of colonial invasions on these lands. This devastation has been profitable to Navajo politicians who seek to maintain our role as a resource colony.

In 2015 the EPA accidentally released more than 3 million gallons of toxic waste from the Gold King Mine into the Animas River. The toxic spill flowed throughout Diné communities polluting the “San Juan” river which many Diné farmers rely on. Crops were spoiled that year. As a measure of relief for the water crisis, the EPA initially sent rinsed out fracking barrels. Chili Yazzie, the former Chapter President of Shiprock stated, “Disaster upon catastrophe in Shiprock. The water transport company that was hired by EPA to haul water from the non-contaminated San Juan River set up 11 large 16,000 gallon tanks throughout the farming areas in Shiprock and filled them up with water for the crops. As they started to take water from the tanks for their corn and melons, the farmers noticed the water from some of tanks was rust colored, smelled of petroleum and slick with oil.”

Resource colonialism specifically targets Indigenous women, two-spirit, and trans relatives, as we see connected though the mass killings addressed through the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans, & Two-Spirits (#MMIWGT2S). #MMIWGT2S is a campaign initiated in so-called “Canada” to address extremely disproportionate and unreported violence against Indigenous womxn. The movement has been extended to Missing and Murdered Girls, Trans and Two-Spirit relatives (MMIWGT2S) due to the alarming levels of gender-based violence that are invisibilized.

#MMIWGT2S initially focused on the link between resource colonialism and gender-based violence. The extractive industry’s “man camps” which are sites at large-scale extractive industry projects where male workers are clustered in temporary housing encampments in areas close to reservations. For years Indigenous communities have raised concerns regarding these issues and only very recently the #MMIWGT2S movement has been more broadly recognized.

Violence of resource colonialism is violence against the land, which is violence against our bodies.

Food Deserts: A Project of Colonial Violence

Our health has been broken by nutritionally-related illnesses imposed by colonial attacks on our cultural food systems. Diné Bikéyah wasn’t a “food desert” until colonization. According to the American Diabetes Association, “People with diabetes do face a higher chance of experiencing serious complications from COVID-19. In general, people with diabetes are more likely to experience severe symptoms and complications when infected with a virus.”

One in three Diné are diabetic or pre-diabetic, in some regions, health care workers have reported diagnosing diabetes in every other patient.

In 2014, Diné organizer Dana Eldrige published a powerful report on Diné Food Sovereignty through the Diné Policy Institute. In the report the concept of the Navajo Nation as a “food desert” was contextualized as a process of colonialism and capitalism.

The report identified a Food Desert as “an area, either urban or rural, without access to affordable fresh and healthy foods. While food deserts are devoid of accessible healthy food, unhealthy, heavily processed foods are often readily available… [Food Deserts] are linked with high rates of nutritionally-related illness. For rural communities, the United States Department of Agriculture has defined rural food desert as regions with low-income populations, the closest supermarket is further than twenty miles away and people have limited vehicle access….Diné people with limited or no income are limited in their food choices, and since

healthy, fresh foods are of greater cost, people with limited financial resources often have no

other option than to purchase low-cost, heavily processed, high calorie foods which lead to the

onset of nutritionally-related illnesses.”

The report found that a majority of participants from Diné communities who participated in the

study had to travel at least 155 miles round trip for groceries while others regularly drove up to 240 miles. There are 13 full service grocery stores in the Navajo Nation, according to the report one of the stores contained 80% processed foods.

The report further stated that “An examination of the Navajo Nation food system reveals that our current food system not only does not serve the needs of the Navajo Nation, but also negatively impacts the wellbeing of the Diné people. These issues include epidemic levels of nutritionally-related illness including diabetes and obesity, food insufficiency (high rates of hunger), significant leakage of Navajo dollars to border towns, disintegration of Diné lifeways and K’é (the ancient system of kinship observed between Diné people and all living things in existence), among other issues; all while the Navajo Nation grapples with extremely high rates of unemployment, dependence on Natural Resource extraction revenue and unstable federal funding.”

Our homelands didn’t become a “food desert” by accident or lack of economic infrastructure, the history of food scarcity in our communities is directly correlated with a history of violent colonial invasion.

After facing fierce Diné resistance in the mid-1800s, “U.S.” troops invaded and attacked Canyon De Chelly in the heart of Diné Bikéyah. They employed “scorched earth tactics” by burning homes along with every field and orchard they encountered. “U.S.” Colonel Kit Carson led a campaign of terror to drive Diné on what is called “The Long Walk” to a concentration camp called Fort Sumner hundreds of miles away in eastern “New Mexico.” The report states:

“Carson’s scorched earth campaign including the slaughtering of livestock, burning of fields and orchards, and the destruction of water sources. This scorched earth policy effectively starved many Diné people into surrender. Word reached those who had not been captured that food was being distributed at Fort Defiance. Many families chose to go to the fort to alleviate their hunger and discuss peace, unaware of Carleton’s plans for relocation. Upon arrival at the fort, the Diné found they could not return back to their homes and were captives of the United States military…Due to failure of crops, restrictions on hunting, and the unavailability of familiar native plants, the Diné had to depend on the United States military to feed them, marking a major turning point in the history of Diné food and self-sufficiency. Food rations were inadequate and extremely poor in nutritional content, consisting primarily of salted pork, cattle, flour, salt, sugar, coffee and lard.”

When colonizers established military forts while waging brutal wars against Indigenous Peoples, they would also provide rations as a means of pacification and assimilation.

The book Food, Control, and Resistance: Rations and Indigenous Peoples in the United States and South Australia illustrates how food rationing programs were a tool of colonization and worked alongside assimilation policies to weaken Indigenous societies and bring Indigenous peoples under colonial control. Once Indigenous peoples became dependent on these food rations, government officials deliberately manipulated them, determining where and when the food would be distributed, restricting the kind and amount of foods that were distributed, and determining who the foods would be distributed to. Starvation was weaponized materially and politically.

The strategy of settler societies was to destroy the buffalo, sheep, corn fields, water sources, and anything that fed Indigenous Peoples to diminish our autonomy and create dependency.

As colonial military strategies increasingly focused on attacking Indigenous food systems, liberation and redistribution of resources was not unfamiliar to our ancestors, they effectively raided colonizer’s supplies and burned their forts to the ground. But clearly the scorched earth strategies were devastatingly effective.

Starting in the 1930’s the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) ordered a reduction of Diné livestock herds. BIA officials killed the herds “and left them to rot, all in front of Diné families. Some herds were even driven off cliffs, while others were doused with kerosene and burned alive.”

This mass killing of animals seriously impaired the self-sufficiency of Diné. Many had to rely on government rations and a growing trading post economy to feed their families. Although the political justification for the extreme reduction was to mitigate soil erosion, the report illustrates that other factors such as “desertification and deteriorating rangeland, such as climatic change, periodic drought, invasion of exotic vegetation, and a drop in water table,” were the primary issues.

In 1968 the first grocery store opened on the Navajo Nation in Tségháhoodzání (Window Rock, “Arizona”).

The report illustrates that:

“the impact of these grocery stores and the decline of Diné foods were documented in nutritional research. By the 1980’s, soda and sweetened drinks, store bought bread, and milk were commonplace in the Navajo Diet, while fry-bread and tortillas, potatoes, mutton, and coffee continued as staples. Although many Navajo families still farmed (corn, squash, and melon reported as the most cultivated crops), gardens were generally small and ‘no longer appeared to be a major source of food for many families…In addition to dietary changes, the shift in Diné life and society also include the breakdown of self-sufficiency, Diné knowledge, family and community, and detachment from land. These changes did not occur by chance, but were fostered by a series of American interventions and policies (the process of colonization); namely forced removal, the livestock reduction, boarding schools, relocation, and food distribution programs, along with the change from subsistence lifestyles to wage based society and integration into American capitalism….Prior to American efforts of colonization, Diné people operated in a food system that was not only integral to our culture, but one in which Diné people actively produced and collected the food needed to feed their communities. This meant that Diné people did not depend on outside governments and systems for food. Not only did the people ensure that quality and nutritious food was provided, but they did so without operating under the authority or governance of these outside entities.”

In the conclusion of the report, the Diné Policy Institute recommended, “revitalizing traditional foods and traditional food knowledge through the reestablishment of a self-sufficient food system for the Diné people.”

In typical fashion, the colonial government and Navajo politicians have deepened the assimilation process through their efforts to reform the food desert issue, by starting a farming initiative that purchases seed from Syngenta and Monsanto and that uses tax incentives to make healthy food more affordable, furthering Dine peoples dependence on commodified food.

Although the Navajo Tribal Council established a mass-scale farming initiative called “Navajo Agricultural Products Industry (NAPI),” the farm has stated on its website that it plants genetic hybrid corn seed purchased from “Pioneer Seed Company, Syngenta Inc., and Monsanto companies.” In 2014, in an attempt to “curb” the diabetes epidemic, the Navajo Nation Council created a law that raised the sales tax for cheap junk foods sold on Navajo Nation and another removing sales tax from fresh fruits and vegetables. Economic pressure on those already struggling while not addressing the root causes and environmental degradation is par for the course for the colonial government and Navajo politicians.

Instead of directly feeding ourselves and communities, we have become dependent on businesses and corporations that are more concerned with profits than our health and well-being. The boarding schools were replete with capitalist indoctrination to forcibly assimilate Diné children into colonial society. The curriculum was designed with a clear lesson: To feed our families we needed jobs. To have jobs we needed to be trained. To be trained we needed to obey. To not have a job means you’re poor. To employ other workers is to build wealth. To build wealth means success.

The process of destroying Indigenous self and collective sufficiency is an ongoing process of capitalist assimilation. Starvation is still weaponized against our people.

We cannot talk about economic deprivation and lack of resources without talking about history, we cannot address the COVID-19 crisis without addressing the crises of capitalism and colonialism. The disappearance & annihilation of Indigenous People has always been part of the project of resource extraction and colonialism.

A Virulent Faith

On March 7, 2020 in the small remote community of Chilchinbeto in Diné Bikéyah, a christian group held a rally and “Day of Prayer” in response to the coronavirus outbreak. According to one report a pastor was coughing during his sermon. On March 17th, the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed on the reservation with Chilchinbeto as the epicenter of a growing outbreak. On the 18th the Nation closed itself to visitors. On March 20, as confirmed COVID-19 cases doubled then tripled, the Navajo Nation issued a shelter-in-place order for everyone living on the reservation and imposed a curfew 10 days later.

As schools were closed in response to the crisis, the Rocky Ridge Boarding School — located on Black Mesa just near lands partitioned in the so-called Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute — stayed open. Staff at the school had participated in the Chilchinbeto Christian rally and its roughly 100 students were exposed to the virus.

This is not the first time that Christians and boarding schools have exposed our lands and Indigenous Peoples to a pandemic. COVID-19 is not the first virus our people have faced.

From measles, smallpox infected blankets, to the influenza epidemic of 1918 (when an estimated 2,000 Diné perished), Indigenous Peoples have long been familiar with the colonial strategies of biological warfare. Some estimates state that approximately 20 million Indigenous People may have died in the years following the first wave of European invasion due to diseases brought by colonizers– up to 95% of the population of the so-called “Americas.” The colonization of the “Americas” was a christianizing strategy codified in the 1493 Papal Bull “Inter Caetera” to ensure “exclusive right” to enslave Indigenous Peoples and take their lands.

As documented heavily in 1763, during an ongoing siege on the colonial military outpost called “Fort Pitt” led by Obwandiyag (Odawa Nation, aka Pontiac), British invaders used smallpox infected blankets as a biological weapon. The British general, Jeffrey Amherst had written, “Could it not be contrived to send the smallpox among those disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, use every stratagem in our power to reduce them.”

In 1845, John Louis O’Sullivan declared the “American” belief in the “God-given mission” of the so-called United States as “manifest destiny.” This idea accelerated the colonial violence of “American” expansion.

Under the so-called “Peace Policy” of “U.S.” President Grant, reservations were to be administered by Christian denominations which were allowed to forcibly convert Indigenous Peoples to Christianity. By 1872, 63 of 75 reservations were being managed by Christian religious groups. The “Peace Policy” also established that if Indigenous Peoples refused to move onto reservations, they would be forcibly removed from their ancestral lands by U.S. soldiers. These white supremacist christain policies led to laws passed by “U.S.” Congress in 1892 against Indigenous religions. Any Indigenous Person who advocated their cultural beliefs, held religious dances, and those involved in religious ceremonies were to be imprisoned.

Total assimilation was also the ultimate goal of the violently dehumanizing “U.S.” boarding school project. It was a religiously based white supremacist process to “kill the Indian and save the man,” with the goal of “civilizing” or compelling Indigenous people to be “productive” members of settler society. Every menial job skill of the subsequent assimilation era represented a rung on a ladder that our people were compelled to climb for their “higher” education took them farther away from our cultural knowledge systems and self/collective reliance further into a system of economic exploitation. It was also a strategy to fulfill land theft through erasure of Indigenous connections and reliance on our lands.

Capitalism is an economic and political system based on profit motive, competition, free market, and private property and is characterized by extreme individualism. It’s genealogy is rooted in slavery, genocide, and ecocide. Resource colonialism is the systematic domination and exploitation of Indigenous lands and lives to benefit the attacking non-Indigenous social order. This is different from settler colonialism, which is the invasion, dispossession, and/or eradication of Indigenous lands and lives with the purpose of establishing non-Indigenous occupation of those lands.

To this end, economic development models to address “poverty” in our communities only mean our people will continue to be dependent and ultimately solidify the arrangement that was established through colonial and capitalist domination of our lands and peoples. The process of “indigenizing” or “decolonizing” wealth in this context only makes us that much more complicit in our own genocide.

The colonial project is largely incomplete as our cultures are incompatible with capitalism. There is no duality of Indigenous and capitalist identity, they exist diametrically opposed as natural and unnatural enemies. Ultimately only one can exist while the other must perish.

In the midst of geopolitical battles for minerals, oil, and gas in the Navajo Nation resource colony, environmentalists have cried for a “just transition” into a “green economy.” By urging for “new deals” to make capitalism more eco-friendly and sustaining unsustainable ways of life through solar or wind energy, all while the underlying exploitative power relationships remain intact. This arrangement doesn’t seek to end colonial relations with resource extractive industries, it red/greenwashes and advances them.

In this way both Navajo Nation politicians and non-profit environmental groups (and even some proclaimed radical ones) are in the same business of fulfilling the expansion of capitalism on our lands.

Throughout our lands of painted deserts, our bleeding is obscured by red ochre sunsets kissing rough brown skin. This is where gods are still at war in the minds of those obsessed with words in books that are not our own. Everything is desecrated. Everything is for sale.

From Mother Earth to our bodies, in capitalism everything has been reduced to a commodity. As long as it can be sold, bought, or otherwise exploited, nothing is sacred. So long as the lands (and by extension our bodies) are viewed this way we will have conflict, as capitalism is the enemy of Mother Earth and all which we hold to be sacred.

Missionizing Charity & Allyship

Diné families in the remote region of Black Mesa on Diné Bikéyah — in particular those impacted by forced relocation — have long been the perpetually “impoverished” fascinations of aspiring white saviors. Self-appointed allies, ranging in political spectrum from anarchists to Christian missionaries have rushed to provide support through “food runs” and other forms of charity. They keep a tidy arrangement providing for some families and leaving others out, building long-term relationships that fill accounts somewhere, all the while providing maintenance to the very system of rationing and control that was set in place during the so-called “Indian Wars.”

This brand of “charity” continues to be a strategy of colonial societies to control Indigenous Peoples throughout the world. Non-profit industry operatives (allies and Indigenous non-profits) missionize capitalist and colonial dependency, all while starving our people of their autonomy. They functionally are the new forts of the old wars.

Settler and resource colonialism and capitalism have been and continue to be the crisis that has dispossessed Indigenous Peoples throughout the world from our very means of survival.

From scorched earth campaigns that intentionally destroyed our fields and livestock and forced us to rely on government and missionary rations, to the declarations of our communities as perpetually “impoverished” disaster zones by Christian groups, non-profit organizations, and even some radical support projects, our autonomy has consistently been under attack. This is exacerbated today by those who perpetuate and benefit from cycles of dependency veiled as acts of “charity.”

In its obscene theater, ally-politics have nearly become a characterization of Dances with Wolves. Whether it’s self-discovery and guilt-distancing decolonial projects or groups such as Showing Up for Racial Justice and the Catalyst Project parachuting to the frontlines of Indigenous struggles (from Big Mountain to Standing Rock), the fetishist settler gaze rarely sees beyond the periphery of its own interests and comfort. In endless workshops and zoom meetings, it centers understandings of resistance and liberation on its own terms. This is most obvious when these false friends chase another social justice paycheck or abandon us when things get hard. The ally-industrial complex is in the process of colonizing Indigenous resistance. “Allies” are the new missionaries.

Settler society is grappling with how to understand and respond to this crisis, but for that to fully occur they have to come to terms with how their ways and understanding of the world has been built on a linear timeline, and how that timeline is coming to an end. Instead of fetishizing this ending with fantasies of apocalyptic survival and savior scenarios, this is the time of dirty hands, it’s a time of direct action, meaningful solidarity and critical interventions. It’s a time of solidarity and ceremony. If we are to have true solidarity and not charity on stolen lands, we must establish reciprocal terms that have a deep understanding of ongoing legacies of colonial violence.

Indigenous Mutual Aid is Necessary

In early March 2020 mutual aid projects started mobilizing in Diné Bikéyah. As of this writing more than 30 groups are coordinating emergency relief in various forms of direct actions throughout our communities.

The idea of collective care and support, of ensuring the well-being of all our relations in non-hierarchical voluntary association, and taking direct action has always been something that translated easily into Diné Bizáad (Navajo language). T’áá ni’ínít’éego t’éiyá is a translation of this idea of autonomy. Many young people are still raised with the teaching of t’áá hwó’ ají t’éego, which means if it is going to be it is up to you. No one will do it for you. Ké’, or our familial relations, guides us so that no one would be left to fend for themselves. I’ve listened to many elders assert that this connection through our clan system, that established that we are all relatives in some way so we have to care for each other, was the key for survival of those who were imprisoned at Fort Sumner. It’s important to also understand that Ké’ does not exclude our non-human relatives or the land.

Indigenous Peoples have long established practices of caring for each other for our existence. As our communities have a deep history with organizing to support each other in times of crisis, we already have many existing models of mutual aid organizing to draw from.

This has looked like a small crew coordinating their relatives or friends to chop wood and distribute to elders. It has looked like traditional medicine herbal clinics and sexual health supply distribution. It has looked like community water hauling efforts or large scale supply runs to ensure elders have enough to make it through harsh winters. It has looked like unsheltered relative support through distribution of clothing, food, and more.

Any time individuals and groups in our communities have taken direct action (not by relying on politicians, non-profit organizations, or other indirect means) and supported others–not for their own self-interests but out of love for their people, the land, and other beings–this is what we know as “mutual aid.”

When we recognize that we’re all in this together, that no one is better than anyone else and we have to take care of each other to survive, this is what anarchists have come to call, “Mutual Aid.” It’s a practice that anarchist author Peter Kropotkin wrote about in his book published in 1902 called “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution.” His analysis was established in large part by observing how Indigenous communities cooperated for survival in contrast to existing European notions that attempted to assert that competition and domination were “natural” human behaviors. Kropotkin understood mutual aid as a law of nature, that when you observe and listen to nature, you understand that life thrives not by struggling for existence or the shallow notion of survival of the fittest, but through mutual support, cooperation, and mutual defense. We never needed and still don’t need dead white men from Europe to instruct us on how to live.

Indigenous Mutual Aid organizing challenges “charity” models of organizing and relief support that historically have treated our communities as “victims” and only furthered dependency and stripped our autonomy from us. We organize counter to non-profit capitalists who maintain neo-colonial institutions and we reject the NGO-ization and non-profit commodification of mutual aid.

While solidarity means actively and meaningfully supporting each other, it also doesn’t mean blind illusions of “unity” or that we must flatten out the diverse cultural and political ways and views that each of us maintains. There are some necessary tensions and factions in our communities and in radical Indigenous politics. Some Indigenous non-profits such as the NDN “Collective” and Navajo & Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund (NHFCRF) have made millions of dollars from relief efforts in response to this pandemic. Relief has become big business while root causes are reinforced and further entrenched. To illustrate the disconnect of analysis, the NHFCRF started distributing coal for Diné and Hopi families to burn to stay warm in the cold depths of winter. Others are proposing a “revolutionary Indigenous socialist” agenda in an academic vanguard charge to proletarianize Indigenous ways through redwashed Marxism. This re-contextualizing of Marx and Engles’ political reactions to European capitalism does nothing to forward Indigenous autonomy. The process inherently alienates diverse and complex Indigenous social compositions by compelling them to act as subjects of an authoritarian revolutionary framework based on class and industrial production. Indigenous collectivities and mutuality exists in ways that leftist political ideologues can’t and refuse to imagine. As to do so would conflict with the primary architecture their world is built on, and no matter how it’s re-visioned, the science of dialectical materialism isn’t a science produced by Indigenous thinking. Colonial politics from both the left and the right are still colonial politics.

As the pandemic of COVID-19 wreaks havoc on our communities and threatens those most vulnerable such as our elders, those with existing health conditions due to colonial diets, ecological devastation, and polluting industries, immunocompromised, unsheltered relatives, and others, there is a clear need for organized mutual aid. Considering the cultural contexts, needs, and especially the history of colonial violence and destruction of our means of self and collective sufficiency, a distinct formation of Indigenous Mutual Aid and Mutual Defense, is necessary.

Indigenous Mutual Aid is not just about redistributing resources, it’s about radical redistribution of power to restore our lifeways, heal our communities, and the land.

Prophecy & Medicine

Just two generations after The Long Walk & mass imprisonment at Fort Sumner, Diné Bikéyah was faced with the influenza epidemic of 1918. Before the outbreak of the flu, my grandmother Zonnie Benally, who was a medicine practitioner, was given a warning when a saddle spontaneously caught fire. After praying she understood that a sickness would come correlated with a meteor shower, and that by eating horse meat she could survive. Zonnie Benally spread the word and urged people to prepare by going into isolation. The sickness also came after a total solar eclipse, which medicine people warned would bring harm to our people.

Dook’o’oosłííd is one of six holy mountains for Diné, we were instructed to live within the boundaries of these pillars that uphold our cosmology. Arizona Snowbowl ski resort has been pumping millions of gallons of treated sewage from the City of Flagstaff to make fake snow on these sacred slopes. Since the Forest Service “manages” the sacred mountain as “public lands,” they sanction this desecration.

Dook’o’oosłííd is one of six holy mountains for Diné, we were instructed to live within the boundaries of these pillars that uphold our cosmology. Arizona Snowbowl ski resort has been pumping millions of gallons of treated sewage from the City of Flagstaff to make fake snow on these sacred slopes. Since the Forest Service “manages” the sacred mountain as “public lands,” they sanction this desecration.

When the initial proposal was made to desecrate the mountain, medicine practitioners testified in court that this extreme disturbance and poisoning of the mountain would have severe consequences for all peoples. Their testimony was prophetic.

Daniel Peaches, member of the Diné Medicine Men’s Association stated, “Once the tranquility and serenity of the Mountain is disturbed, the harmony that allows for life to exist is disrupted. The weather will misbehave, the ground will shift and tremble, the land will no longer be hospitable to life. The natural pattern of life will become erratic and the behaviors of animals and people will become unpredictable. Violence will become the norm and agitation will rule so peace and peacefulness will no longer be possible. The plants will not produce berries and droughts will be so severe as to threaten all existence.”

In 1996 two holy people visited an elder near Rocky Ridge where the Black Mesa outbreak occurred. They had been visiting and sharing messages for some time, & when Sarah Begay, the daughter of the elder came home one day, she saw the holy beings. All of the messages that had been shared were verified by Hataałiis (medicine practitioners). It became a situation because the family’s ancestral lands were claimed in a constructed “land-dispute” with the Hopi tribe. Albert Hale, then Navajo Nation president (who has recently passed due to COVID-19) even declared a “day of prayer.” Their message was prophecy. It spoke of the elders & times we live in now. There were conditions set & what they spoke has unfolded.

The Diné Policy Institute Food Sovereignty Report also found prophecy in their study, “‘…it is said that the Holy People shared with the Diné people the teachings of how to plant, nurture, prepare, eat and store our sacred cultivated crops, such as corn. The importance of these teachings to our well-being was made clear in that the Holy People shared that we would be safe and healthy until the day that we forgot our seeds, our farms, and our agriculture. It was said that when we forgot these things, we would be afflicted by disease and hardship again, which is what some elders point to as the onset of diabetes, obesity and other ills facing Diné people today.’”

In response to ongoing attempts to remove her from her land and confiscate her livestock, Roberta Blackgoat stated, “This land is a sacred land. The man’s law is not our law. Nature, food and the way we live is our law. The plans to disrupt and dig out sacred sites are against the Creator’s law. Our great ancestors are buried all over, they have become sand, they have become the mountains and their spiritual presence is still here to guide us… We resist in order to keep this sacred land in place. We are doing this for our children. ”

Pauline Whitesinger, a Diné matriarch in the resistance against forced relocation on Black Mesa once said, “Washington D.C., is the cause of a lot of hardship and disaster. It’s like a human virus with side effects.”

When I asked my father Jones Benally, a medicine practitioner, what he thought of this current crisis he said, “I’ve been telling you to prepare for this.” And he has, especially since another recent solar eclipse. He said, “The government won’t take care of us. They’re part of the reason nature is attacking.”

We have survived massacres and forced marches, we have endured reservations and boarding schools, we have faced forced sterilizations and national sacrifice zones. We have resisted attacks on Mother Earth as we have long held that the balance and harmony of creation is intrinsically tied to our wellbeing and the health of all living beings. Our immune systems are compromised due to colonial diets and ecocide. From abandoned uranium mines poisoning our lands and waters, to coal mining, fracking, oil pipelines, and desecration of our most sacred sites, we have become more susceptible to this and other diseases due to capitalism and colonialism.

Our prophecies warned of the consequences for violating Mother Earth. Our ways of being have guided us through the endings of worlds before. We listen now more than ever to our ancestors, the land, and our medicine carriers. In these times we care for each other more fiercely than ever. We are living the time of prophecy. The systems that precipitated this disharmony will not lead us through or out of it, they will only craft new chains and cages. As the sickness ravages our lands, we must ask ourselves, “will we continue to allow this empire to recuperate?”

I’ve grown up in a world of ruins. We have teachings and prophecies of the endings of cycles, but that’s always how it’s been here, in this world of harmony and disharmony and destruction. Diné teach this as Hózhóji and Anaaji.

An anti-colonial and anti-capitalist world already exists, but as my father says, “there aren’t two worlds, there is just one world with many paths.” Colonial and capitalist paths are linear by design. In this space between harmony and devastation, we listen to these cycles, we listen to the land, and we conspire. If the path of greed, domination, exploitation, and competition doesn’t accept that it’s reached its dead end, then it is up to us to make sure of it.

+ + + +

Patreon Thank you’s:

Mason Runs Through, Theo Koppen, Andy Wombat, Natasha & Shea Sandy, Cease Wyss, Kim B., Dianna Cohen, Jules Marsh, Fariha Huriya, Katie Sellergren, Rhyannon Curry, Simone Is, Marco Amador, kamryn, Ryan carroll, Desier Galjour, Mary Valdemar, Dara Biswas Glanzer, Yousseph El Boujami

Building Momentum in Resistance to Grand Canyon Uranium Mining & Transport

Originally posted at www.haulno.org

Photos by Dustin Wero | Instagram: darth_wero

In late 2016 Indigenous anti-nuke & sacred sites organizers decided something had to be done to confront the threat of radioactive uranium ore transport from the Grand Canyon to the White Mesa Mill. In December of 2016, volunteer-based Haul No! was formed to raise awareness, organize, and take action to protect sacred lands, water, and our health from this toxic threat. Haul No! got to work right away researching, creating outreach materials, exploring and advocating policy changes, and planning for direct action to stop the transport.

In March 2017, Energy Fuels Inc. (EFI), the owner of Canyon Mine and White Mesa Mill (the only commercially operating uranium processing plant in the US), announced that it could be ready to start mining uranium as early as June 2017. Haul No! kicked into gear and started organizing an awareness and action tour along the 300-mile planned haul route, coordinating with community hosts along the way.

BLUFF, UT – SHUT DOWN WHITE MESA MILL

Haul No! initiated the tour on June 13, 2017 in Bluff, Utah. Although we started the event a bit later than intended (our crew was converging from a range of different points in the Southwest), the Bluff Community Center had an energetic crowd of 35 people. Our tour presentation consisted of two parts: the first, on facts relating to Canyon Mine, the haul route, and White Mesa Mill; the second was Indigenous-rooted direct action training.

The conversations centered around White Mesa Mill, which is located just 20 miles to the north of Bluff. White Mesa Mill was built in 1979 to process uranium ore from the Colorado Plateau. Since then, it has processed and disposed of some of the most toxic radioactive waste produced in the U.S. In 1987, it began processing “alternate feed material” (uranium-bearing toxic and radioactive waste) from across North America. Energy Fuels disposes of the mill’s radioactive and toxic waste tailings in “impoundments” that take up about 275 acres next to the mill. The mill is built on sacred Ute Mountain Ute lands. More than 200 rare and significant cultural sites are located on the mill site. When the mill and its tailings impoundments were constructed, several significant cultural sites were destroyed.

The conversations centered around White Mesa Mill, which is located just 20 miles to the north of Bluff. White Mesa Mill was built in 1979 to process uranium ore from the Colorado Plateau. Since then, it has processed and disposed of some of the most toxic radioactive waste produced in the U.S. In 1987, it began processing “alternate feed material” (uranium-bearing toxic and radioactive waste) from across North America. Energy Fuels disposes of the mill’s radioactive and toxic waste tailings in “impoundments” that take up about 275 acres next to the mill. The mill is built on sacred Ute Mountain Ute lands. More than 200 rare and significant cultural sites are located on the mill site. When the mill and its tailings impoundments were constructed, several significant cultural sites were destroyed.

The White Mesa Mill is currently undergoing renewal of its Byproduct Radioactive Material License (RML UT1900479) and the Groundwater Quality Discharge Permit for the White Mesa Uranium Mill. Utah Department of Environmental Quality held 2 public meetings in June, in Salt Lake City and Blanding.

A dozen community members from the nearby Ute Mountain Ute community of White Mesa, Utah joined the Haul No! tour stop and shared their experiences. Ephraim  Dutchie spoke about the spiritual quality of of the land and the environmental racism they experience not just from the Mill workers, but also from pro-Mill residents and law enforcement. “The don’t care about our community they only care about money. White Mesa is not the only community that will be affected by this. Keep water pure and land sacred.” Ephraim said.

Dutchie spoke about the spiritual quality of of the land and the environmental racism they experience not just from the Mill workers, but also from pro-Mill residents and law enforcement. “The don’t care about our community they only care about money. White Mesa is not the only community that will be affected by this. Keep water pure and land sacred.” Ephraim said.

Bluff and White Mesa community members also expressed great concern that their drinking water will be contaminated by further milling operations. The Navajo Sandstone aquifer lies right beneath the mill site. Other comments included concerns about accidents, leaks, and the liners of the tailings impoundments (such as quality, maintenance, and replacement).

The following day, the Haul No! crew, comprising of Leona Morgan, Sarana Riggs, Klee Benally, Dustin Wero, and Bobby Mason, met up with Ute Mountain Ute organizers at the entrance to White Mesa Mill. Haul No! volunteer Leona Morgan, who also works with Diné No Nukes and Radiation Monitoring Project, donned her hazmat suit & mask to monitor radioactive pollution at the entrance of the mill. When mistaken for being simply a photo-op, Leona said, “I’m not just messing around guys…I’m really working here.”

In the past two years alone, two radioactive spills have occurred en route to the mill. Both involved haul trucks from the Cameco Resources uranium mine in Wyoming and spill in march that spread radioactive barium sulfate sludge along U.S. Highway 191.

After Dustin took some pictures with Haul No! crew & Ute Mountain Ute defenders, part of the crew went directly to the Mill site to bring the message that we want them to shut down. Yolanda Badback confronted EFI workers as law enforcement agents arrived. Apparently  there was a call made regarding trespassing and vandalism. Yolanda stated, “This was our land and now it’s poisoned, Energy Fuels has no right to be here.” Our crew is adept at dealing with law enforcement encounters so there were no issues aside from a warning.

there was a call made regarding trespassing and vandalism. Yolanda stated, “This was our land and now it’s poisoned, Energy Fuels has no right to be here.” Our crew is adept at dealing with law enforcement encounters so there were no issues aside from a warning.

We ate and slept well that night thanks to our gracious hosts in Bluff. We look forward to returning.

TAKE ACTION: Send your own comments regarding renewals of White Mesa Mill’s permits. Public comment period ends on July 31, 2017. Click here for more info & a form letter, you can also email your comments directly to: dwmrcpublic@utah.gov

OLJATO, UT/MONUMENT VALLEY/KAYENTA, AZ – A LEGACY OF ABANDONED URANIUM MINES

Our next stop on the tour took us to Oljato, Utah, which is located within the iconic Monument Valley. Our crew split forces for event set-up and outreach at Kayenta Flea Market. The Oljato event turned into a planning session with a radio interview thrown in. Although the Chapter President assisted us with scheduling the event, no one showed; but that didn’t

Our crew split forces for event set-up and outreach at Kayenta Flea Market. The Oljato event turned into a planning session with a radio interview thrown in. Although the Chapter President assisted us with scheduling the event, no one showed; but that didn’t  dampen our spirits. We knew the community had already passed a strong resolution opposing transport and has long been plagued by abandoned uranium mines. Oljato Chapter was actually the first to pass such a resolution in December 2016. In fact, the feature documentary Return of Navajo Boy, which is partly responsible for triggering the Navajo Nation 5-year clean up program, focused on a family living in Monument Valley.

dampen our spirits. We knew the community had already passed a strong resolution opposing transport and has long been plagued by abandoned uranium mines. Oljato Chapter was actually the first to pass such a resolution in December 2016. In fact, the feature documentary Return of Navajo Boy, which is partly responsible for triggering the Navajo Nation 5-year clean up program, focused on a family living in Monument Valley.

In Oljato/Monument Valley, we did more one-on-one outreach and education regarding the issue, to the Navajo Utah Commission, market vendors, and the Chapter Vice President.